Abstract

Wayfinding is a participatory installation that serves as a poetic reference to the design concept that describes the ways in which people navigate from place to place. The installation is comprised of a set of four electromechanical sculptures that operate in subsequent harmony and discord based on participant and environmental impulses. Each sculpture, positioned at a cardinal direction, operates independently by way of a motor that strikes tensed bungee cables containing a glass orb with a glass marble. In effect, both movement and sound ensue and the sequence and speed at which the motors fire is continuously manipulated by proximity sensors that poll the environment and mine through data collected throughout the installation’s exhibition history. Through the installation’s symbolic embodiment of a compass, the work seeks to reflect on the socio-technological forces that guide our direction in life.

Media

Overview

By paying homage to the design principle of wayfinding (Lynch, 1960) coupled with underlying themes in metamorphosis and actor-network theory (Latour, 1996), this responsive installation invites participants to engage in a dialogue where their presence shapes the information transmitted to an electro-mechanical compass that serves as a reflection on the paths one chooses in life, and how subtle nudges from the environment transmitted through technological means can result in subsequent periods of chaos and harmony.

The installation is comprised of a set of four electromechanical sculptures that function based on environmental impulses. Each sculpture, positioned at a Cardinal Direction, operates independently by way of a servomotor that strikes taut bungee cables containing a glass orb with a glass marble. The resulting effect produces both movement and mechanical sound. Software manipulates and morphs the sequence at which the sculptures fire (both starting point and delay time), inviting participants to meddle with the notion of direction amidst time.

The physical component of the piece serves as the starting point of the interaction model. Each sculpture contains an ultrasonic range finder sensor, which detects motion and proximity. The motors fire in a sequence, the starting point of which is dependent on real-time and historic data captured from each sensor, and then stored on a server. The closer a participant is to a particular sculpture, the more likely it is to start a sequence from that direction. Additionally, the algorithm takes a running average of all distances captured from the ultrasonic range finders and maps it to the rest period between sequences. When more participants are present in the field of each sensor, the resulting data captured leads to more democratic effects, which toy with participants’ mental model of how the installation provides feedback. In this sense, action is the form (Easterling, 2015), and the action of the objects (i.e., actuator sequence) imbue meaning, which can be interpreted as a direct analogy to the unpredictability of life and the potential impact our interactions with others may have on our sense of space and time.

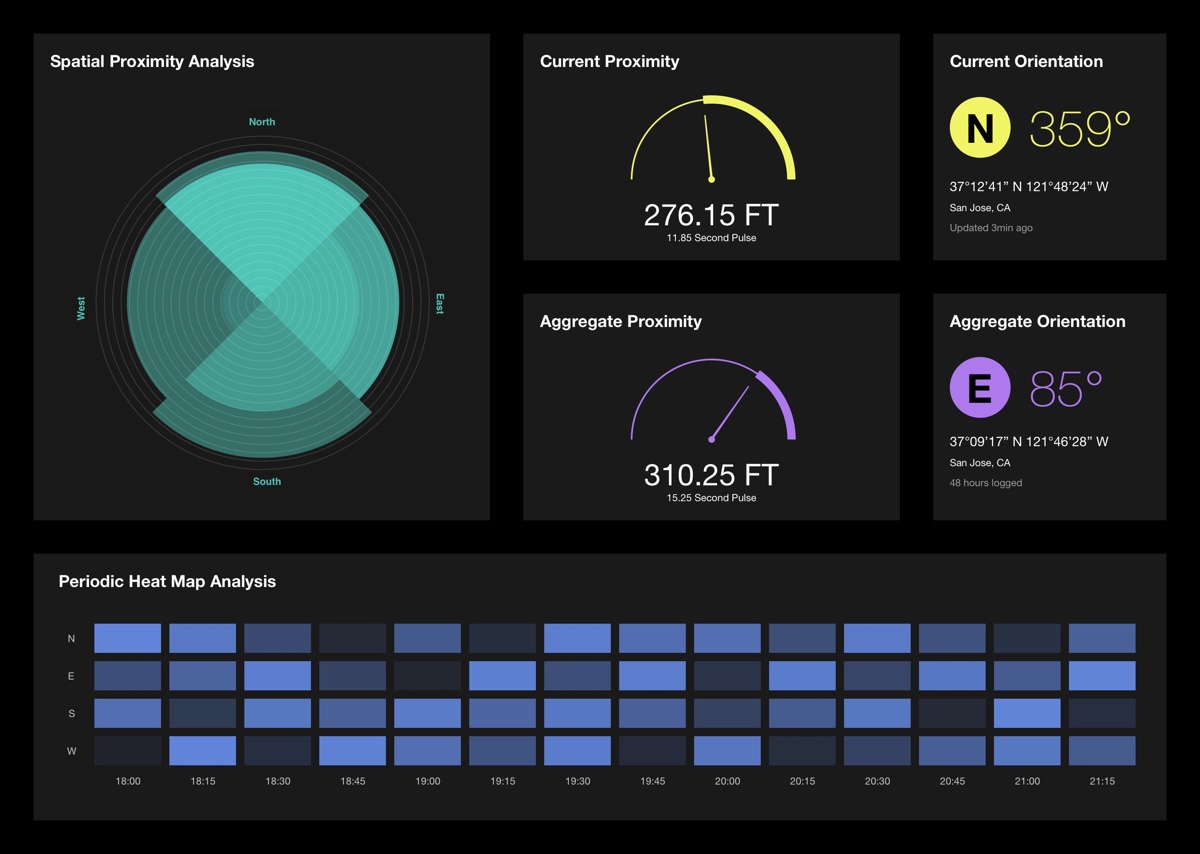

While the physicality of the work serves as a means to generate data, a digital projection placed behind the sculptures serves to visualize both real-time and historic data captured. During the course of the work’s exhibition history, proximity and motion data have been captured from the sensors. The data visualization entails a modular design to allow participants to glean visual insight from the installation’s sensors. As a result, a feedback loop exists between the physical and digital. The physical component serves as a means to generate data by starting a conversation with participants, while the digital component serves as a means to visualize it. Thus, the audience become actors in a loose feedback loop between data generation and data visualization that can be repeated indefinitely in order to find new meaning.

References

- Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. MIT Press, Cambridge, 1960.

- Latour, Bruno. On actor-network theory: a few clarifications. Soziale Welt, 47, 4 (1996), 369-381.

- Easterling, Keller. An Internet of Things. In Aranda, Julieta et al., eds., E-flux Journal: The Internet Does Not Exist. Sternberg Press, 2015.